Seizing the Future: The Imperative for Militaries to Master AI and Forge Strategic Alliances

Panel members Keith Dear, Al Brown, Sofia Gaston and Alessio Patalano discuss UK-Japanese relations and digital transformation at the Farnborough International Airshow 2024

Militaries must seize the benefits of rapid technological advances or risk being left behind. To succeed, they must meet the challenges of AI and other rapidly advancing technologies while embracing the opportunities of innovative international partnerships such as the UK-Japan Hiroshima Accord.

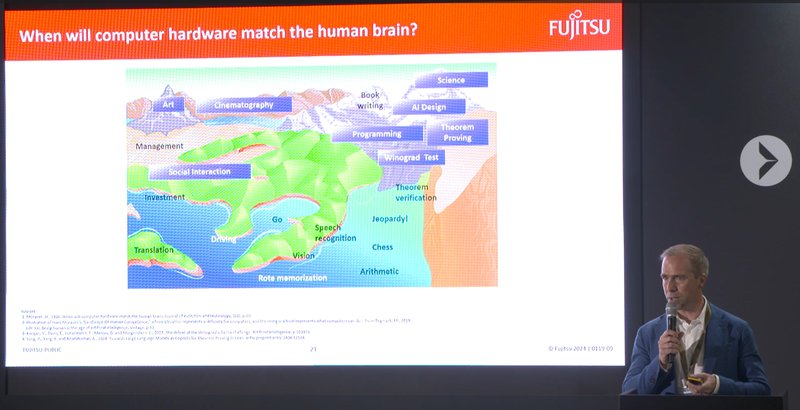

In a keynote address at the Farnborough International Airshow in July, Keith Dear, Managing Director of Fujitsu’s Centre for Cognitive and Advanced Technologies, outlined the current pace of technological change, particularly in artificial intelligence (AI).

He pointed to research from McKinsey that shows the current rate of innovation, disruption, and technological advance is 30 times the speed, 300 times the scale, and 3000 times the impact of the Industrial Revolution.

The impact is transformative. In AI, for instance, the volume of computational power applied to training models increased by 300,000 times between 2012 and 2018. The same rate of development in a mobile phone battery would see it go from one day on a single charge to enduring for 800 years.

However, in the six years since, the rate of development has increased: if applied once again to a phone battery, it would now last 100 million years on a single charge.

Innovation wars

Against this backdrop, companies and countries have been plunged into an era of innovation wars. The consequences of success and failure could not be more serious: according to Dear, we are approaching a point of ‘innovation escape velocity’, specifically in the fields of generative design and automated manufacturing.

‘If you lose that competitive advantage in generative design and automated manufacturing, you may never regain it: you will get innovation and scientific runaways,’ Dear said.

To seize the advantage, we need a new theory of winning, explained Dear. This means determining how we want to fight and developing technology to meet those ambitions – not the other way around. It means embracing the potential of technology that does not yet exist – and making it a reality.

This is not a new concept. Dear explained the impact of Frederick Lindemann, prime scientific adviser to Winston Churchill, whose ideas were often frustrated by the War Office. However, his work with Churchill helped establish the Tizard Committee, which drove the development of the Dowding System to control and protect UK Airspace, a classic example of producing technology to meet particular goals.

More recently, the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) pursued its Assault Breaker concept from 1978, aiming to address the potential threat from huge numbers of second echelon Soviet forces in a potential European ground war: this led directly to today’s concept of network-enabled warfare.

However, despite the obvious and recent benefits of such an approach, it is not in evidence today. The absence of such a coherent strategy could even be seen at Farnborough itself, according to Dear.

‘There are some incredible technologies, but it's like we've got all the different pieces of the jigsaw puzzle and no idea what the picture looks like … when it's fully assembled,’ he said. ‘We need that theory of winning if we’re to transform defence with technology that does not exist.’

Keith Dear delivers a keynote address on the theory of winning at FIA 24

Partnering for success

The nations that seize technological leadership in AI could hold it on a permanent basis. To succeed in a world of increasingly advanced peer rivals who are actively seeking a technological advantage of their own, Western nations and their allies must enhance their partnerships.

That was the focus of the panel session ‘The UK and the defence of Japan: turning the Hiroshima Accord into action’, featuring experts from academia and industry.

Sophia Gaston is Head of Foreign Policy and UK Resilience and lead of the AUKUS industry forum at Policy Exchange. She outlined three major components of the Hiroshima Accord.

First is the doctrine of indivisibility between the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific security theatres. This is ‘one of the most significant developments over the past decade: these two G7 powers have really taken up that mantle’, Gaston said.

The second major theme of the partnership is the integration of economic and national security objectives, Gaston said, particularly around advanced technology and innovation.

‘This is another area in which we don't just share the same outlook: we have the same diagnosis about the instruments and assets that we have to respond to them,’ she said, with both nations placing such capabilities at the heart of their economic growth strategy and their national security agendas.

Finally, Gaston pointed to a focus on net zero and clean energy, which is tied into the advanced technology story.

‘There is a moral mission to this. It is about the international order, because this is an issue that brings the whole global community together and in which both countries feel we have a leadership stake.’

Alessio Patalano, Professor of War and Strategy in East Asia at the Department of War Studies in King’s College London, said the UK and Japan have long had a good defence relationship. Until recently, they had different priorities, with the UK focusing on the War on Terror and Japan prioritising threats from state actors, notably North Korea and China.

However, there has been a significant alignment in world views, as seen through the UK’s Integrated Review of 2021 and Japan’s 2022 National Security Strategy: while non-state threats have not disappeared, state-on-state contestation is now a key challenge for both countries.

Second, Patalano said Japan and the UK have each recast their sense of self and their international role, with the UK increasingly focused on the Indo-Pacific and Japan looking beyond its traditional focus on Northeast Asia.

And third, both are reshaping their perception of advanced capabilities and their role in national security, particularly in terms of the need for partnerships. Because of their industrial, scientific and technological resources, ‘finding each other became natural’, said Patalano.

No easy answers

Al Brown, Director of Neurosymbolic AI at Fujitsu’s Centre for Cognitive and Advanced Technologies, pointed to the regional challenges Japan faces.

While this obviously includes China and North Korea, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine also represents ‘another step towards realising the potential risks’ of the region. This also ties into the indivisibility of the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific.

Brown echoed Fujitsu colleague Dear, pointing to the impact of the changing pace of technological advances. The Japanese Self-Defense Forces have a large and capable navy and the second-largest numbers of F-35s in the world.

And yet, as with the UK and other nations, they are concerned about the threat of emerging technologies, with even poorer nations and non-state groups – such as those that operate in Yemen – having access to UAVs and ballistic missiles.

Success comes down again to the need for a new approach to marshalling and exploiting the rapid pace of technological advance, Brown noted.

‘There are no easy, nice, simple [answers],’ Brown said. ‘Japan has to face the same sort of challenge and threat that I think people here [in the UK] are struggling with as well.’

Collaboration between like-minded, advanced nations is essential to succeed in a world of transformative technology, notably generative design and automated manufacturing. As Dear noted in his keynote address:

‘We must win. If we lose, we may never regain the advantage. If we win, we may never lose it.’

More from Studio

-

![Combat-proven capabilities: How precision-strike systems are evolving for tomorrow’s battlespace (podcast)]()

Combat-proven capabilities: How precision-strike systems are evolving for tomorrow’s battlespace (podcast)

Combat-tested technology is being reshaped to counter A2/AD threats, reduce reliance on GPS and enable faster, more autonomous targeting in complex environments. In this special podcast, experts explain how the evolving threat landscape is shaping next-generation strike capabilities.

-

![Energy evolution: How laser defence systems are powering the next phase of air defence (podcast)]()

Energy evolution: How laser defence systems are powering the next phase of air defence (podcast)

Laser-based air defence is moving from promise to deployment as global threats evolve. In this special podcast, we explore how high-energy laser systems are reshaping interception strategies.

-

![Intelligence advantage: How real-time GEOINT is reshaping military decision-making (Studio)]()

Intelligence advantage: How real-time GEOINT is reshaping military decision-making (Studio)

In today’s contested operational environment, adaptability is key. The new Geospatial-Intelligence as a Service (GEO IaaS) solution from Fujitsu and MAIAR empowers militaries by enabling intelligence advantage, combining advanced technology with human expertise to deliver actionable insights.

-

![Training Together: Unlocking Educational Excellence through Military and Industry Collaboration (Studio)]()

Training Together: Unlocking Educational Excellence through Military and Industry Collaboration (Studio)

Military training is ultimately about people. At Capita, training programmes are built on close engagement with partners, delivering an educational approach that can adapt to individual needs, cultivate leadership – and drive wider cultural change.

-

![Enhancing Military Training Through Digital Technology (Studio)]()

Enhancing Military Training Through Digital Technology (Studio)

Digital technologies offer huge opportunities for defence training. However, militaries must adopt an agile approach, placing the needs of their organisations and personnel at the centre of their efforts.

-

![Layered Defence: How new technologies are enhancing armoured vehicle survivability and manoeuvrability (Studio)]()

Layered Defence: How new technologies are enhancing armoured vehicle survivability and manoeuvrability (Studio)

As modern threats evolve, armoured fighting vehicles face a new era of challenges, from loitering munitions to kinetic energy projectiles. Advances in active, passive, and reactive protection systems are crucial to ensuring battlefield dominance, freedom of manouver and vehicle survivability.